More than 1/3 of people over age 51 have at least 1 AK lesion6

Those with 10 lesions or more have a 3-fold increase in the risk for progression to skin cancer6

AK progression isn’t always visible3

At earlier stages, AKs can be more easily felt than seen7

AK is the most common precursor of iSCC1,2

AK lesions at any stage, severity, or depth have the potential to progress to iSCC with a reported progression risk between .025% and 16%4,8,9

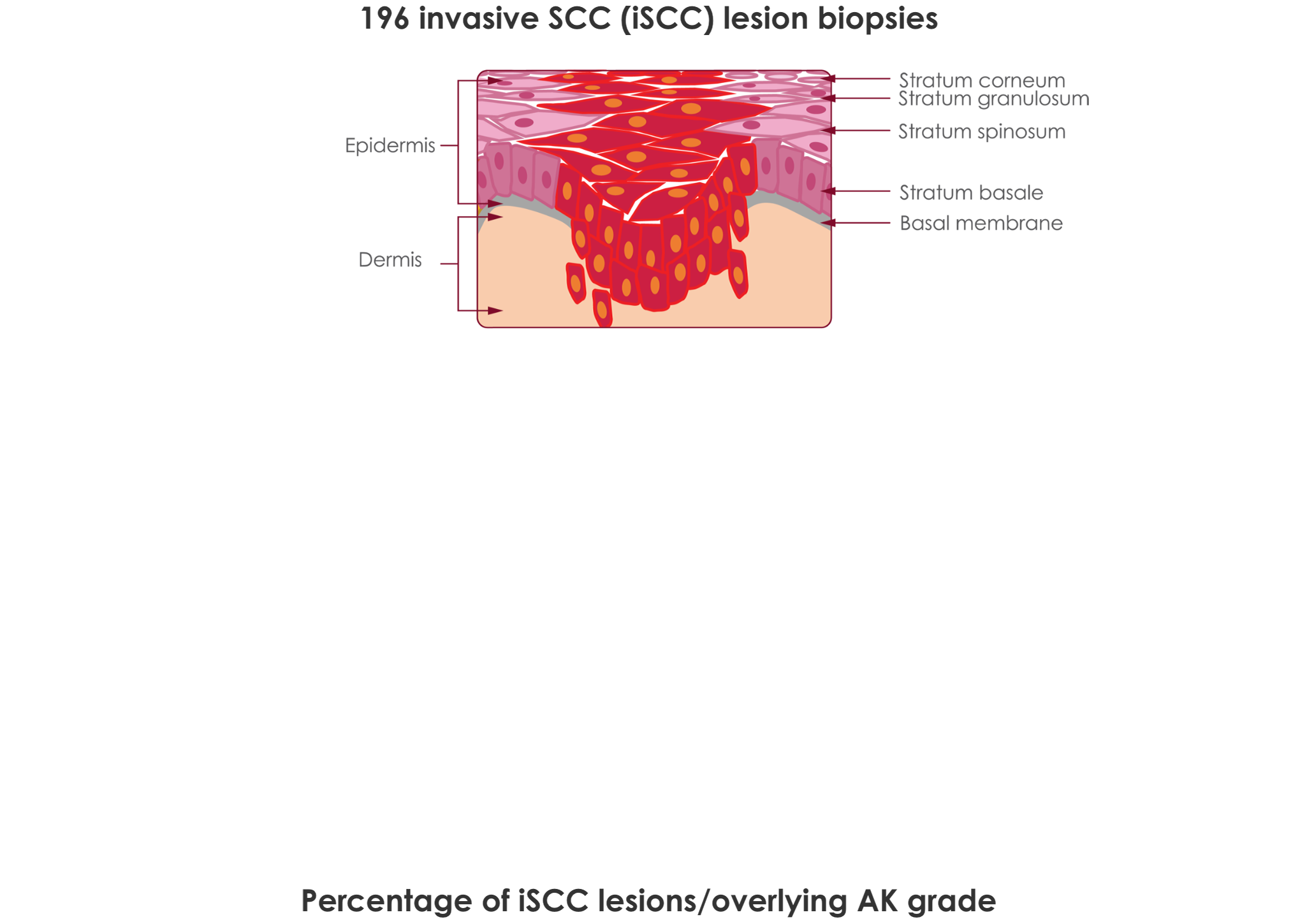

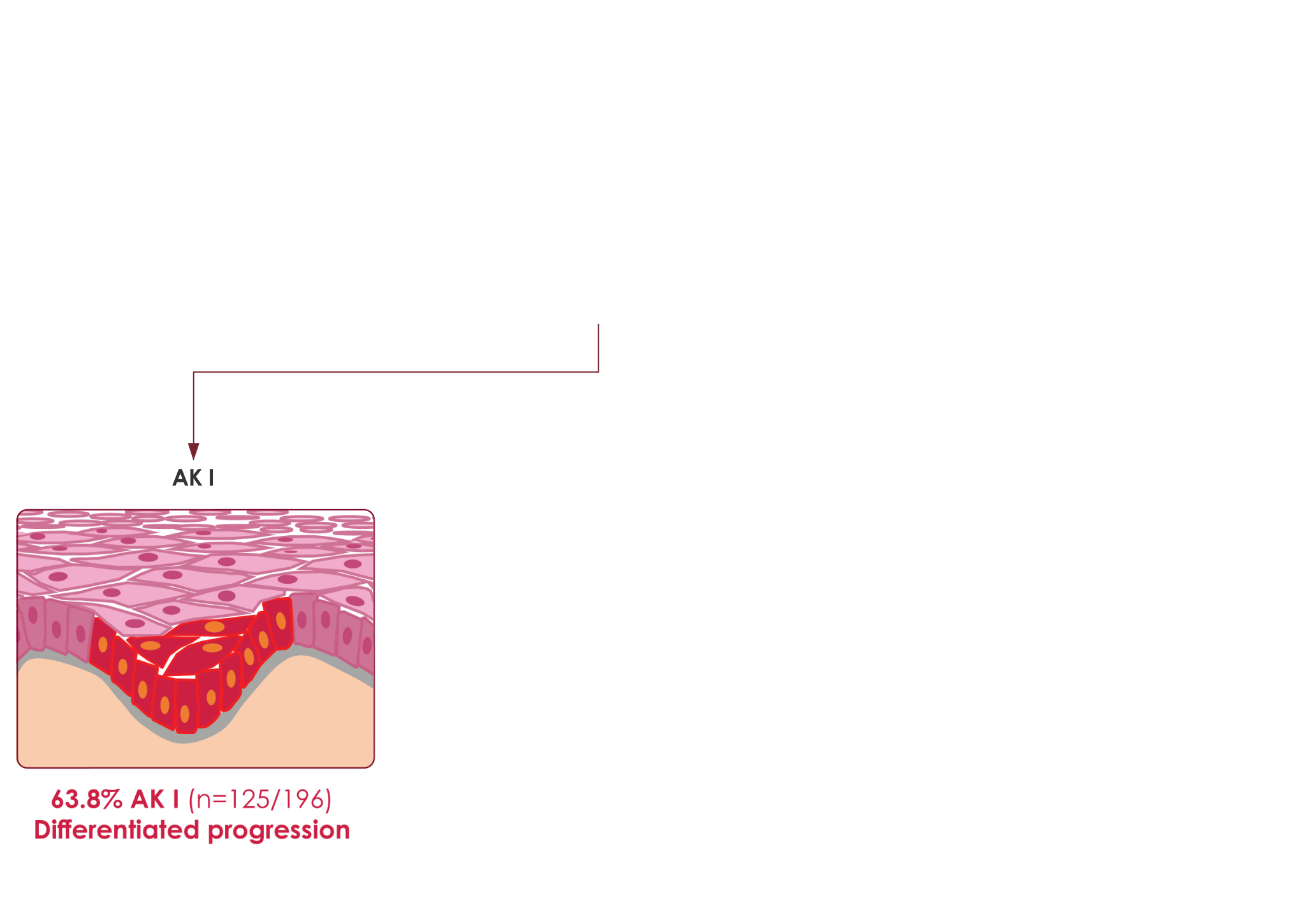

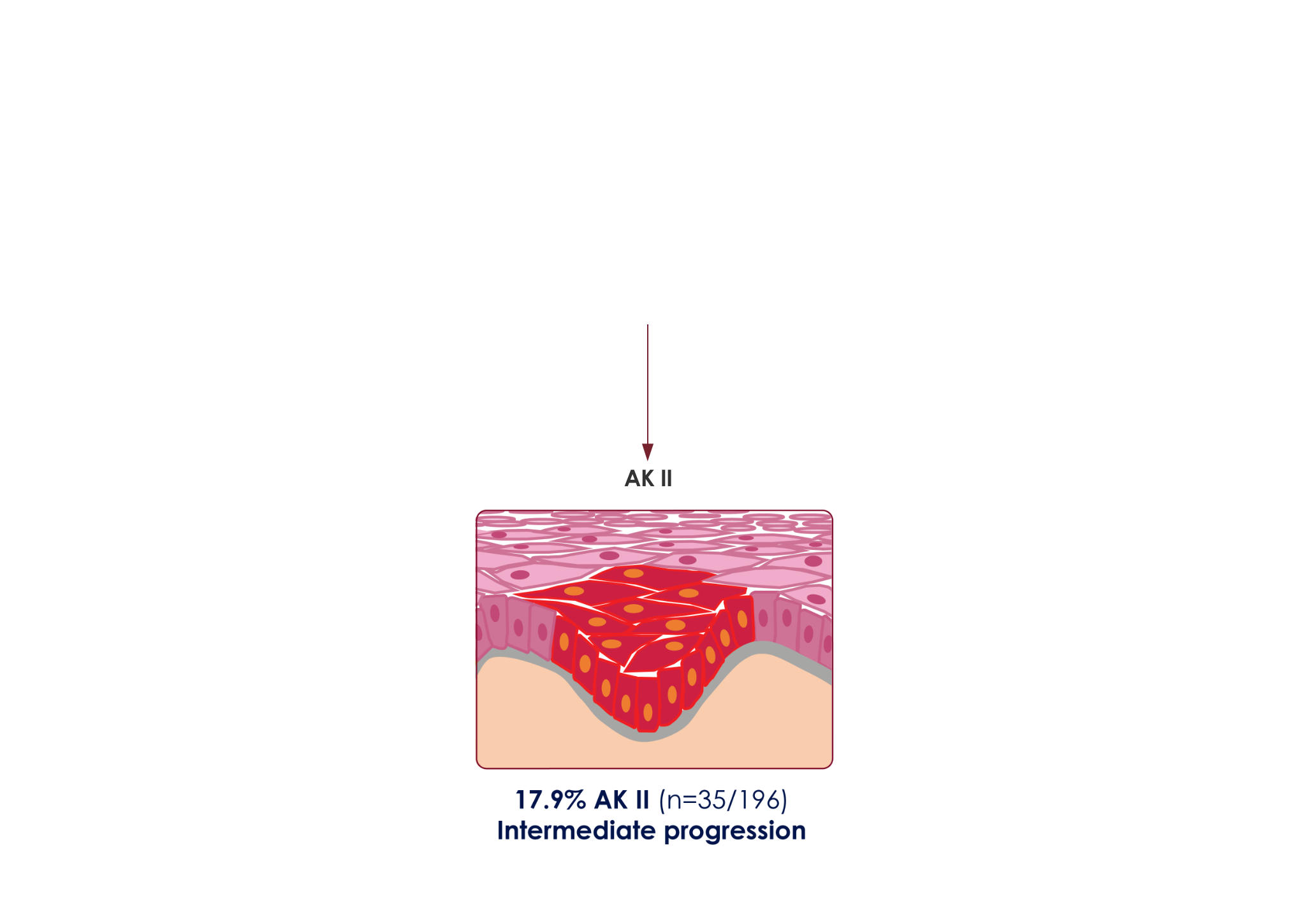

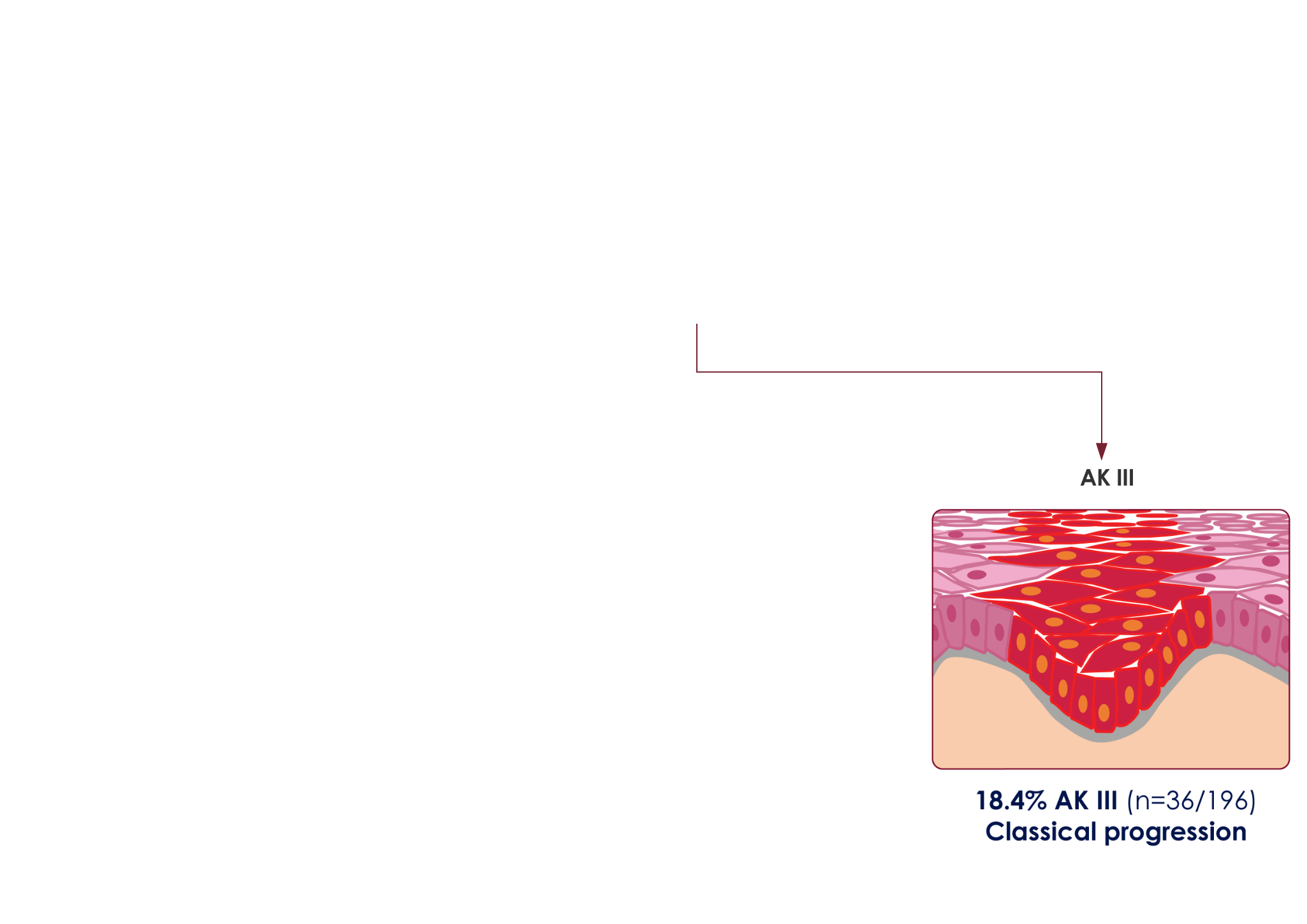

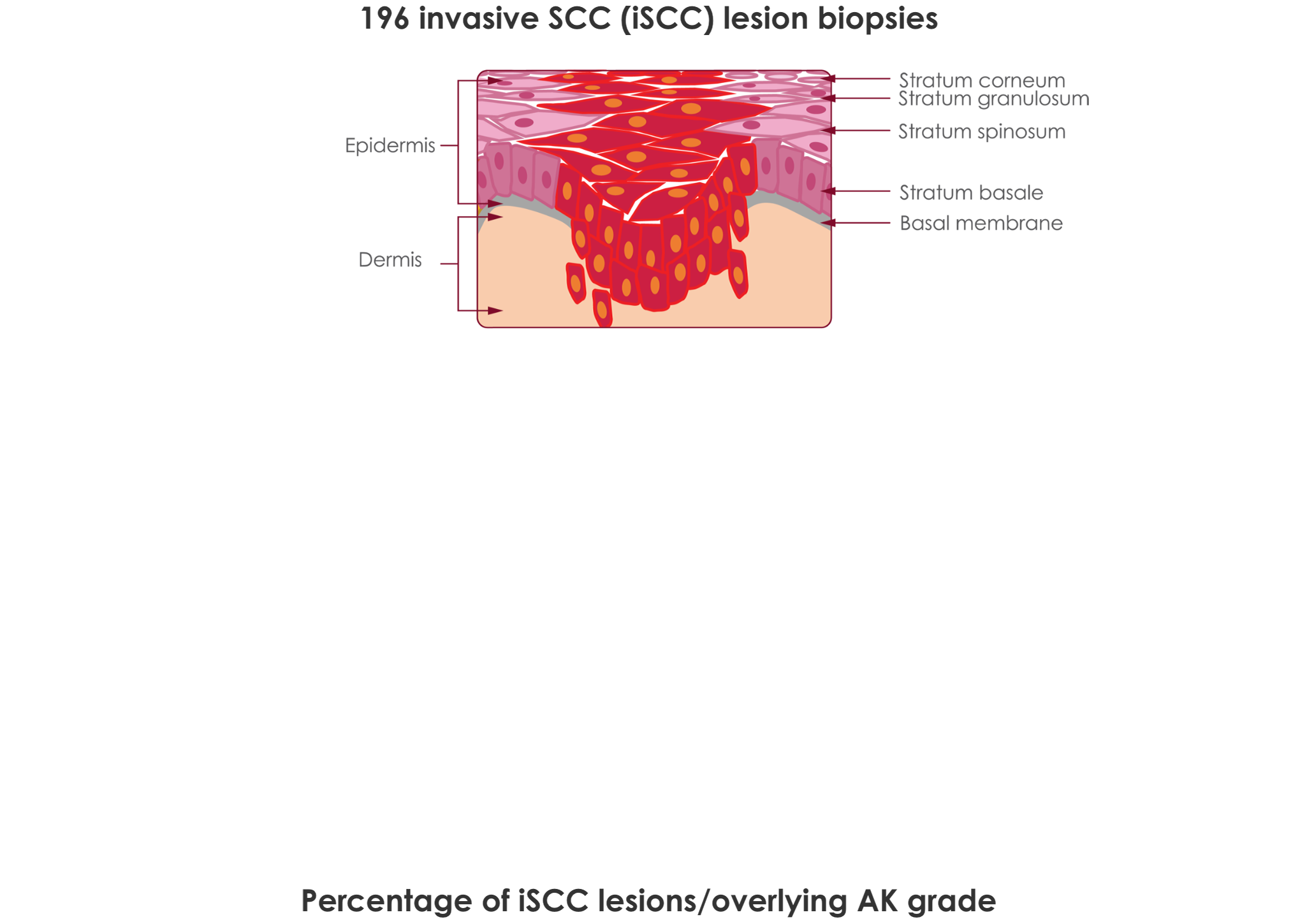

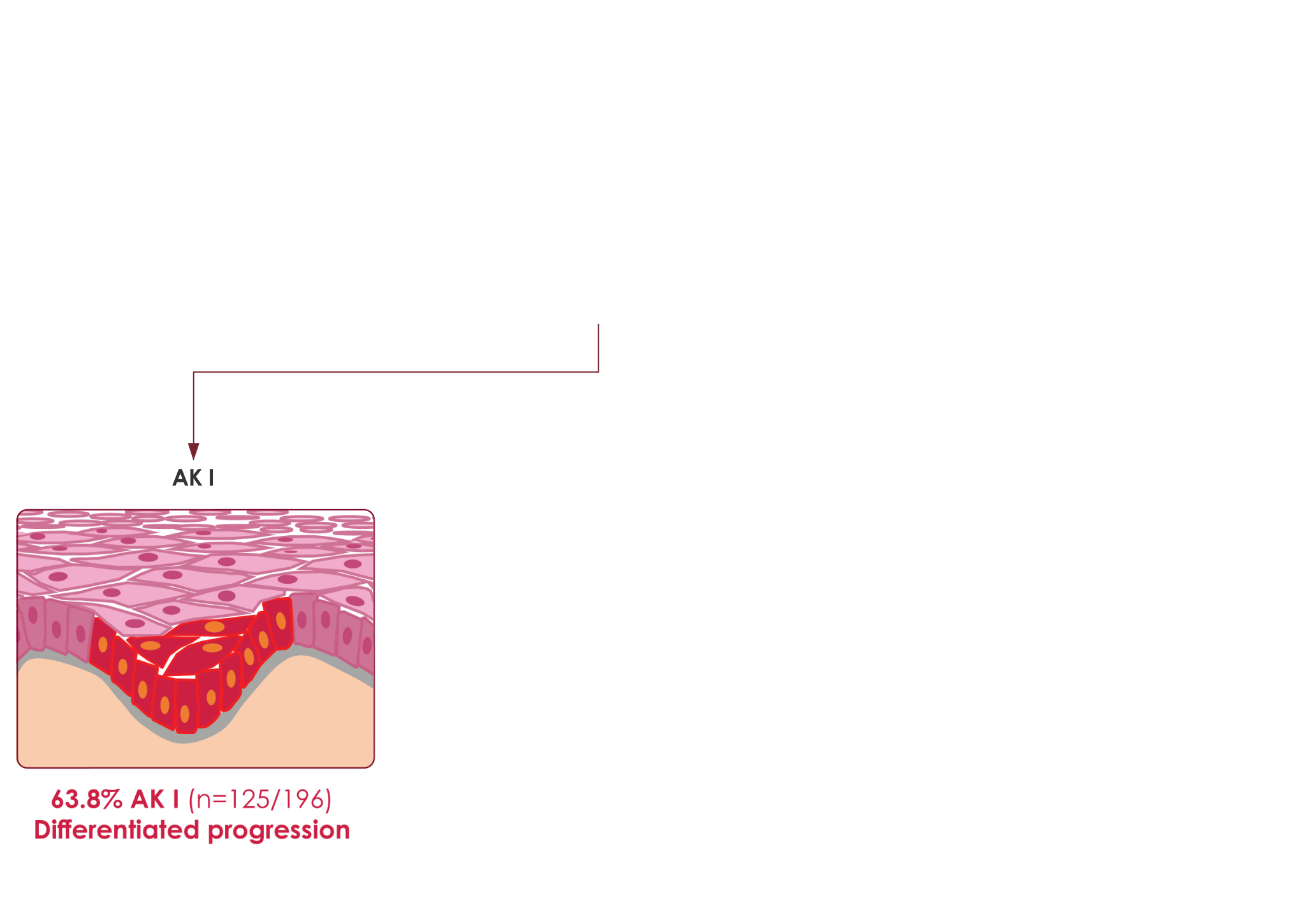

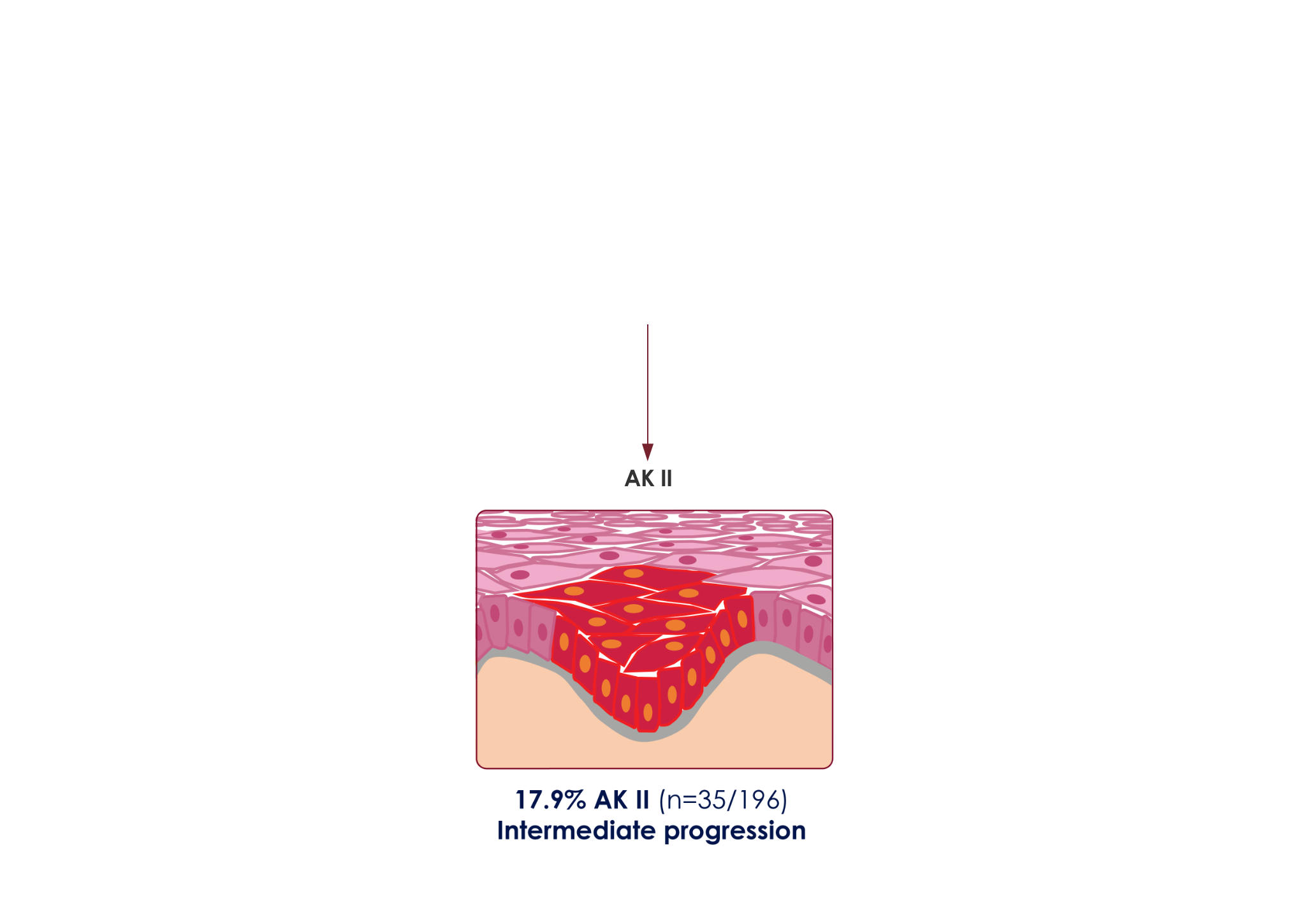

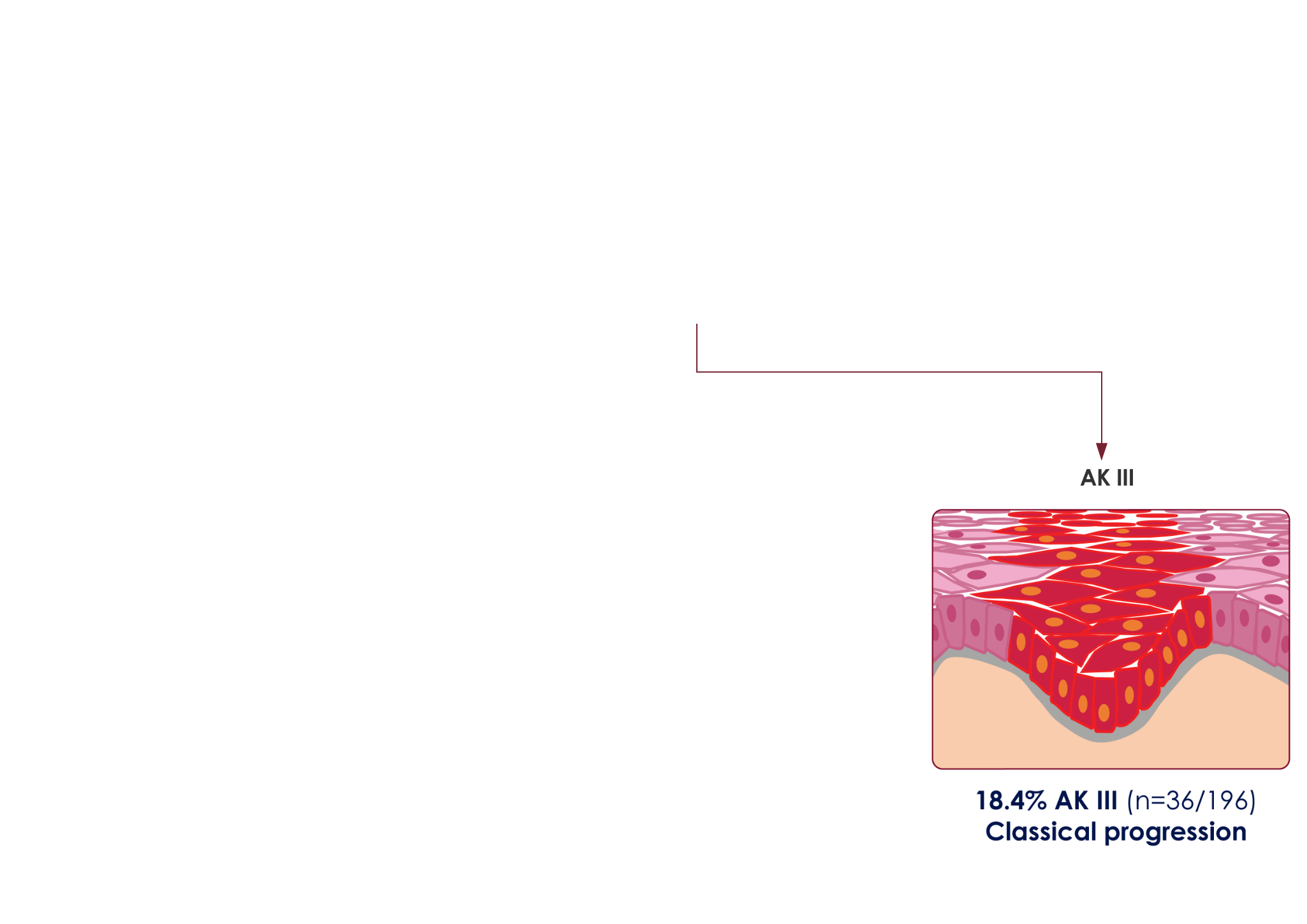

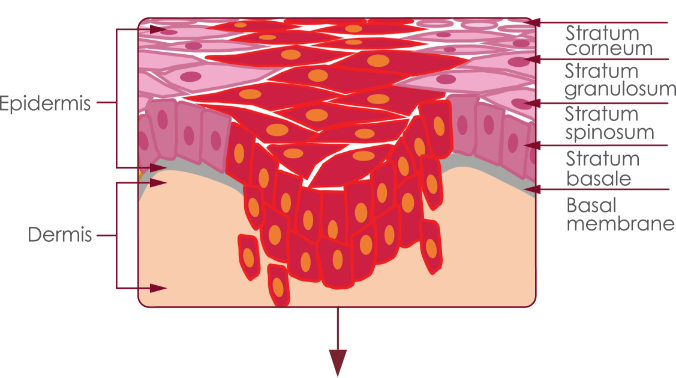

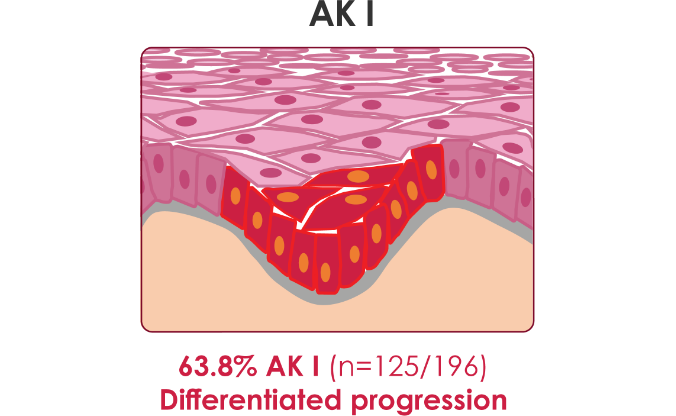

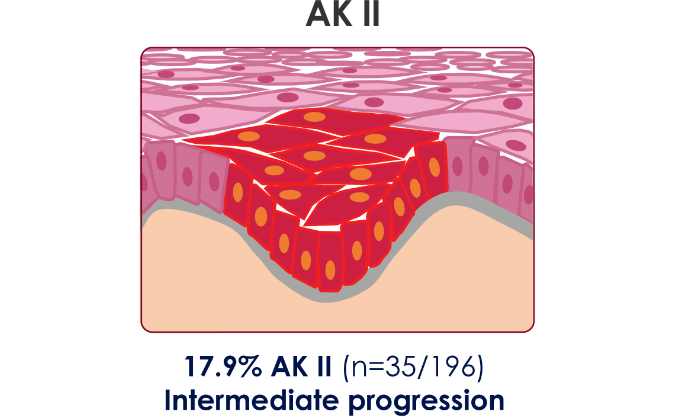

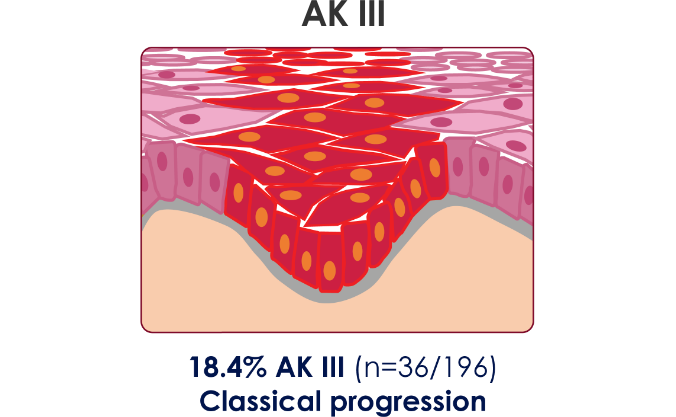

(model derived from Fernández-Figueras et al., 2015)

This model was derived from results of a relatively small study size of 196 skin biopsy specimens, taken at a single center, and does not provide a universal representation of iSCC pathogenesis. Thickness of the epidermal proliferation of atypical keratinocytes overlying the tumor and at its edges was studied. The 196 iSCCs were then assigned to a group (AK I, II, III) depending on the highest AK grade with which they were associated.1

More than 1/3 of people over age 51 have at least 1 AK lesion6

+Those with 10 lesions or more have a 3-fold increase in the risk for progression to skin cancer6

−AK progression isn’t always visible3

+At earlier stages, AKs can be more easily felt than seen7

−AK is the most common precursor of iSCC1,2

+AK lesions at any stage, severity, or depth have the potential to progress to iSCC with a reported progression risk between .025% and 16%4,8,9

−(model derived from Fernández-Figueras et al., 2015)

This model was derived from results of a relatively small study size of 196 skin biopsy specimens, taken at a single center, and does not provide a universal representation of iSCC pathogenesis. Thickness of the epidermal proliferation of atypical keratinocytes overlying the tumor and at its edges was studied. The 196 iSCCs were then assigned to a group (AK I, II, III) depending on the highest AK grade with which they were associated.1

More than 1/3 of people over age 51 have at least 1 AK lesion6

+Those with 10 lesions or more have a 3-fold increase in the risk for progression to skin cancer6

−AK progression isn’t always visible3

+At earlier stages, AKs can be more easily felt than seen7

−AK is the most common precursor of iSCC1,2

+AK lesions at any stage, severity, or depth have the potential to progress to iSCC with a reported progression risk between .025% and 16%4,8,9

−(model derived from Fernández-Figueras et al., 2015)

This model was derived from results of a relatively small study size of 196 skin biopsy specimens, taken at a single center, and does not provide a universal representation of iSCC pathogenesis. Thickness of the epidermal proliferation of atypical keratinocytes overlying the tumor and at its edges was studied. The 196 iSCCs were then assigned to a group (AK I, II, III) depending on the highest AK grade with which they were associated.1

AMELUZ®, in combination with photodynamic therapy (PDT) using BF-RhodoLED® or RhodoLED® XL lamp, a narrowband, red light illumination source, is indicated for lesion-directed and field-directed treatment of actinic keratoses (AKs) of mild-to-moderate severity on the face and scalp.

AMELUZ® containing 10% aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride, is a non-sterile gel formulation for topical use only. Not for ophthalmic, oral, or intravaginal use.

AMELUZ®, in conjunction with lesion preparation, is only to be administered by a health care provider. Refer to BF-RhodoLED® or RhodoLED® XL user manual for detailed lamp safety and operating instructions and adhere to all safety instructions for patient and medical personnel while conducting PDT. Photodynamic therapy with AMELUZ® involves preparation of lesions, application of the product, occlusion and illumination with BF-RhodoLED® or RhodoLED® XL.

Apply an approximately 1 mm thick layer of AMELUZ® to skin lesion(s). Cover individual lesions or the entire AK-field. Include approximately 5 mm of the surrounding skin. The application area should not exceed 60 cm2 and no more than 6 grams of AMELUZ® (3 tubes) should be used at one time. Lesions that have not completely resolved shall be retreated 3 months after the initial treatment.

AMELUZ® shall not be used by persons who have known hypersensitivity to porphyrins or any of the components of AMELUZ®, which includes soybean phosphatidylcholine. AMELUZ® should also not be used for patients who have porphyria or photodermatoses.

Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported with the use of AMELUZ® prior to photodynamic therapy (PDT). If allergic reaction occurs, wash off AMELUZ® and institute appropriate therapy. Inform patients and their caregivers that AMELUZ® may cause hypersensitivity, potentially including severe courses (anaphylaxis).

Transient Amnestic Episodes have been reported during postmarketing use of AMELUZ® in combination with PDT. If patients experience amnesia or confusion, discontinue treatment. Advise them to contact the healthcare provider if the patient develops amnesia after treatment.

Eye exposure to the red light of the BF-RhodoLED® or RhodoLED® XL lamp during PDT must be prevented by protective eyewear. Direct staring into the light source must be avoided. Ophthalmic Adverse Reactions (Eyelid edema and dry eyes) have occurred after PDT with AMELUZ®. Avoid direct contact of AMELUZ® with the eyes. Rinse eyes with water in case of accidental contact.

AMELUZ® increases photosensitivity. Patients should avoid sunlight, prolonged intense light (e.g., tanning beds, sun lamps) on lesions and surrounding skin treated with AMELUZ® for approximately 48 hours following treatment whether exposed to illumination or not.

Special care should be taken to avoid bleeding during lesion preparation in patients with inherited or acquired coagulation disorders. Any bleeding must be stopped before application of the gel. AMELUZ® (aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride) topical gel, 10% should not be used on mucous membranes or in the eyes.

Local skin reactions at the application site were observed in about 99.5% of subjects treated with AMELUZ® and narrow spectrum lamps in three phase 3 trials with a maximal dose of 1 tube of AMELUZ® (2 g) and the application area was up to 20 cm2. The very common adverse reactions (≥10%) during and after PDT were application site erythema, pain/burning, irritation, edema, pruritus, exfoliation, scab, induration, and vesicles. Most adverse reactions occurred during illumination or shortly afterwards, were generally of mild or moderate intensity, and lasted for 1 to 4 days in most cases; in some cases, however, they persisted for 1 to 2 weeks or even longer. Severe pain/burning occurred in up to 30% of treatments.

In two open label clinical trials with 3 tubes (6 g) of AMELUZ® applied to a 60 cm2 area on the face and scalp, most adverse reactions observed were consistent with those reported in trials using one tube (2 g) on a 20 cm2 area. Additional reactions which occurred in ≥1% of subjects when three tubes (6 g) were applied to a 60 cm2 area included dry eyes, photosensitivity, and application site discoloration, dryness, papules, and fissures. The frequencies of certain adverse reactions at the application site in these trials—exfoliation, itching, scab, and erosion—were more than 10% higher with the larger dose (3 tubes, 6 g) and treatment area (60 cm2) compared to the frequencies observed in the trials for the smaller dose (1 tube, 2 g) and area (20 cm2). Severe application site pain was reported by 41% of the subjects treated with three tubes (6 g) on a 60 cm2 area. Most cases were reported during PDT illumination. A total of 15% of subjects discontinued illumination due to adverse reactions.

There have been no formal studies of the interaction of AMELUZ® with other drugs. Concomitant use of the following photosensitizing medications may increase the phototoxic reactions after PDT: St. John’s wort, griseofulvin, thiazide diuretics, sulfonylureas, phenothiazines, sulphonamides, quinolones, and tetracyclines.

There are no available data on AMELUZ® use in pregnant women to inform a drug associated risk. No data are available regarding the presence of aminolevulinic acid in human milk, the effects of aminolevulinic acid on the breastfed infant or on milk production. Safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients below the age of 18 have not been established as AK is not a condition generally seen in the pediatric population. No overall differences in safety or effectiveness were observed between elderly and younger patients, but greater sensitivity of some older individuals cannot be ruled out.

References: 1. Fernández-Figueras MT, Carrato C, Sáenz X, et al. Actinic keratosis with atypical basal cells (AKI) is the most common lesion associated with invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:991–997. 2. Criscione V, Weinstock M, Naylor M, Luque C, Eide M, Bingham S. Actinic keratoses natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the veterans affairs topical tretinoin chemoprevention trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523–2530. 3. Berman B, Amini S, Valins W, Block S. Pharmacotherapy of actinic keratosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(18):3015–3031. 4. Stockfleth E. The importance of treating the field in actinic keratosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(Suppl 2):8–11. 5. Reinhold U. A review of BF-200 ALA for the photodynamic treatment of mild-to-moderate actinic keratosis. Future Oncol. 2017;13(27):2413–2428. 6. Flohil C, van der Leest R, Dowlatshahi E, Hofman A, de Vries E, Nijsten T. Prevalence of actinic keratosis and its risk factors in the general population: the Rotterdam Study. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(8):1971–1978. 7. Olsen EA, Abernethy L, Kulp-Shorten C, et al. A double-blind, vehicle-controlled study evaluating masoprocol cream in the treatment of actinic keratoses on the head and neck. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:738–43. 8. Fernandez Figueras MT. From actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma: pathophysiology revisited. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(Suppl 2):5–7. 9. Schmitz L, Kahl P, Majores M, Bierhoff E, Stockfleth E, Dirschka T. Actinic keratosis: correlation between clinical and histological classification systems. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(8):1303–1307.